When airspace volumes were originally created and designed, we only had to contend with manned aircraft. Unmanned aircraft were not considered. Since then, remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) of all sorts and sizes have emerged, but the legacy airspace designs have not adapted to these new aircraft and their missions. I will concentrate here on airport control zones.

Control Zones

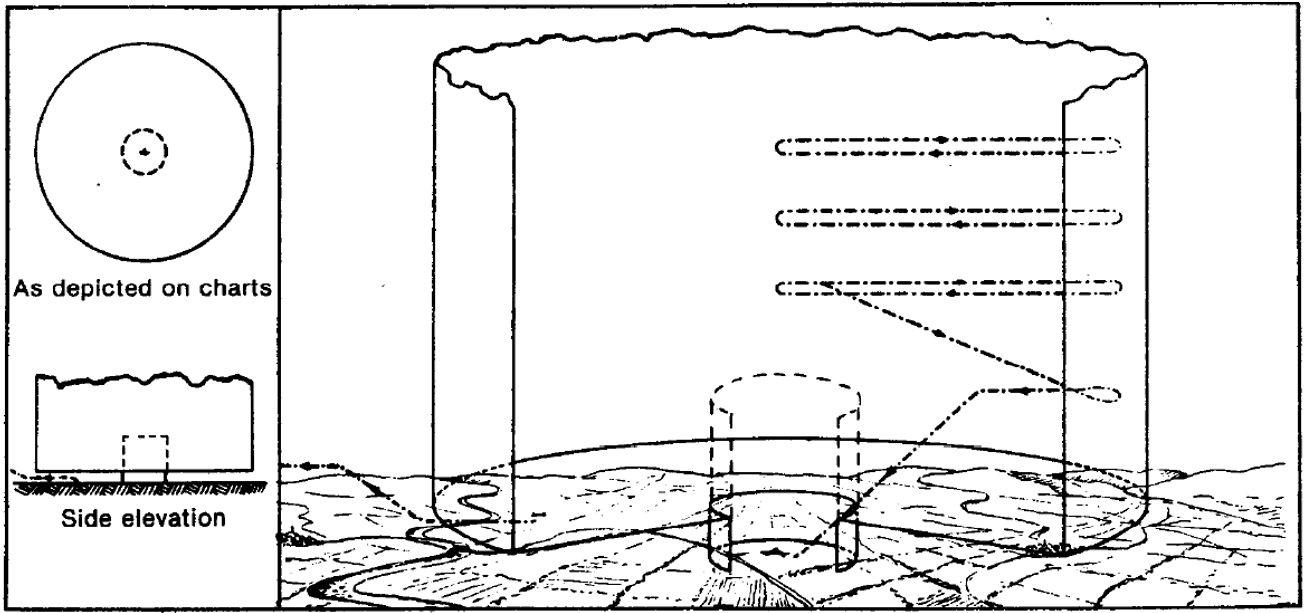

Traditionally, airport control zones have been – and continue to be – constructed as cylinders of controlled airspace originating at the surface (SFC) and extending to a certain height above airport elevation (AAL). This is often some 3000 feet (900 m). The cylinder usually has a radius varying from 3 nautical miles (5 km) to 7 nm (13 km) or even 10 nm (18.5 km), depending on circumstances.

Figure 1 an ICAO diagram depicting a generic airport control zone.

Figure 1 an ICAO diagram depicting a generic airport control zone.

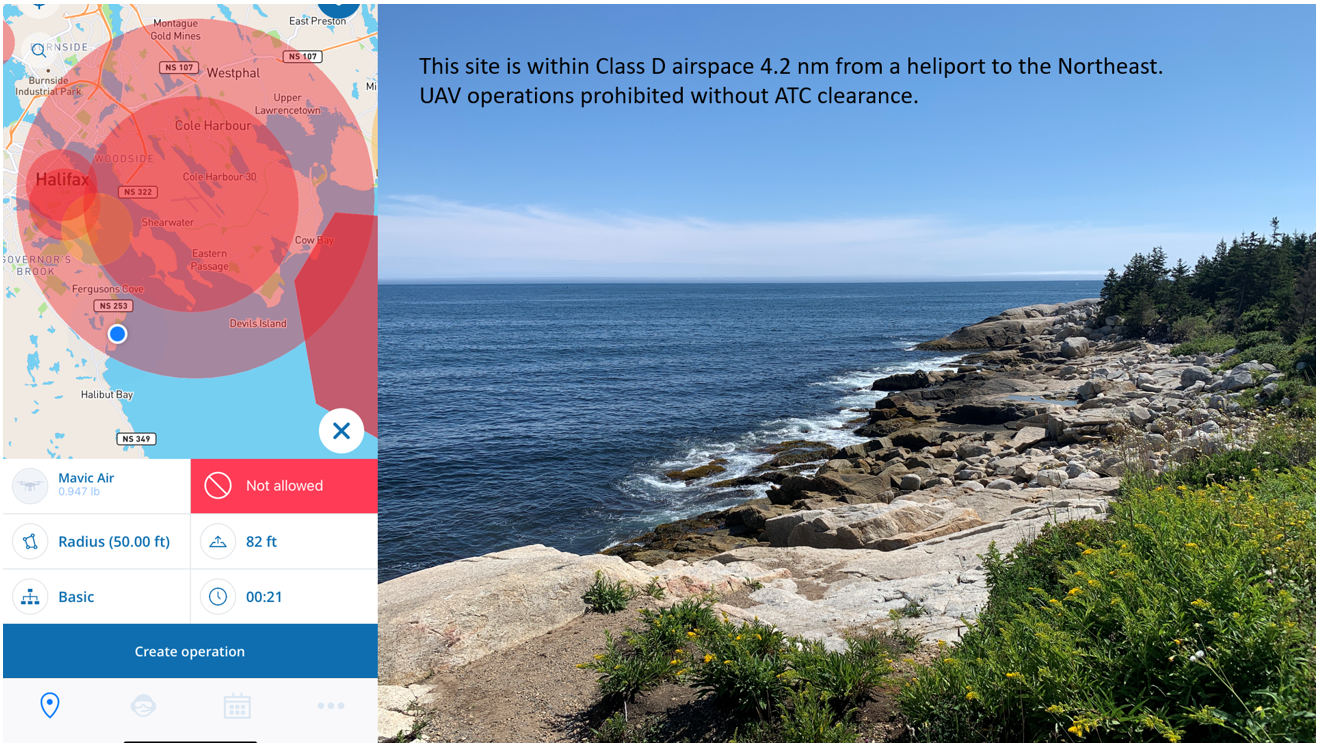

Some control zone designs are complex polygons built to accommodate adjacent control zones or other operational circumstances. In most cases, there is no variability of the base of controlled airspace. It originates at the surface of the earth. Being controlled airspace (often B or C or D depending on states) an air traffic control clearance and direct communications with the air traffic control tower are required to operate at ANY altitude above the surface.

Figure 2 RPA operations are prohibited at any altitude at this location without professional licensing and ATC clearance.

Figure 2 RPA operations are prohibited at any altitude at this location without professional licensing and ATC clearance.

Who are the traditional users of control zones?

Those manned aircraft are either operating on instruments, complying with clearances or instructions, and following specific trajectories, or they’re operating visually (general aviation, government, surveys, etc.) in potentially more random patterns but typically at least at 1000 feet above ground and not below 500 feet above nearby obstacles unless landing or taking off.

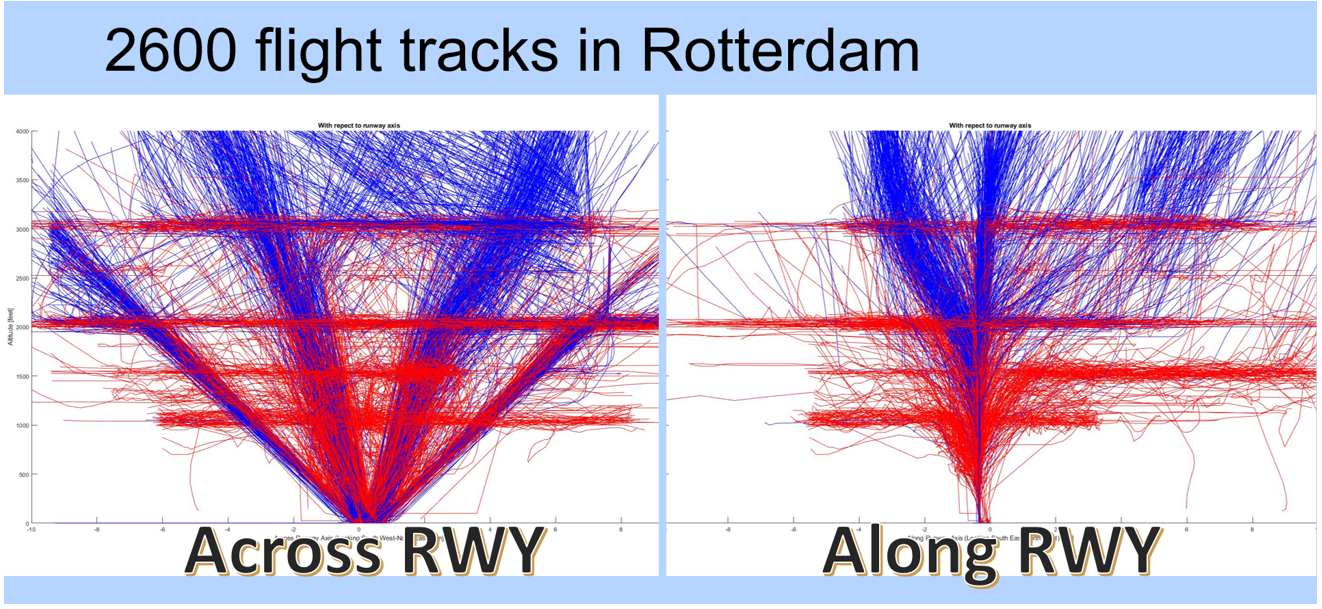

A recent surveillance study of 2600 Rotterdam flights clearly shows the glide path and much steeper climb profiles in the left (perpendicular to runway) view and the very narrow distribution of trajectories in the right (end on) view. The occasional low altitude excursions depict helicopter operations to helipads.

Figure 3 ADS-B survey of 1300 VFR and 1300 IFR trajectories in the vicinity of Rotterdam, NL.

Figure 3 ADS-B survey of 1300 VFR and 1300 IFR trajectories in the vicinity of Rotterdam, NL.

Why do we classify Airspace? Control zones exist to enable ATC to accomplish their function of preventing collisions between aircraft. Airspace classifications were developed over time to set access, capability, and rule requirements to allow ATC to accomplish the function of preventing collisions between aircraft. The creation of controlled airspace is justified when there is significant demand causing traffic density and increased risks of collisions. Controlled airspace does not exist everywhere, nor is it needed.

How do we make decisions on Airspace Designs and Classifications?

Airspace designers and regulators determine where and how to design and classify airspace volumes using aeronautical studies of actual and anticipated traffic demand. Until now, these designs have been made using a broad brush. The reasons for this are simple: we have not had a need to do otherwise, and we haven’t had the tools to gather and analyze the data effectively.

Emerging Airspace Users – RPA

We now have emerging classes of airspace users. Notable among these are commercial space and Remotely Piloted Aircraft. I’m limiting myself here to the RPA. ICAO’s Global Air Traffic Management Operational Concept (Doc 9854) states ICAO’s vision as “to achieve an interoperable air traffic management system, for all users during all phases of flight [bolding of text is mine], that meets agreed levels of safety, provides optimum economic operations, is environmentally sustainable and meets national security requirements.” It’s my view that we are not yet treating all RPAs equitably.

Again, using ICAO concepts, airspace users can either be integrated with each other or segregated. This is nothing new. If airspace users are to be integrated, they should have compatible communications, navigation and surveillance capabilities. They should follow the same rules and behave in a manner compatible with the other users. If airspace users are not to be integrated together, they should operate in segregated, reserved, volumes. This has been the case for military operations and other special cases. I would argue that there is no need to segregate RPAs in low demand density airspace volumes, but we do need to redesign those volumes that are currently airport control zones.

Next steps

What do I believe we should now do? Examine how airspace near airports is used by the manned aircraft. Where do they, and do they need to, operate? How low do they fly and where? And then, for those volumes where there is no need to control the airspace for safety reasons, redesignate the airspace as uncontrolled. This will allow the hobbyists and professionals, such as real estate photographers and construction area surveyors, to carry out their low altitude Visual Line of Sight operations equitably and safety, without excessively onerous burdens being placed on them for no reason other than uninformed fear and suspicion.

Going Forward

I’ve written this blog post to generate a discussion. Is the current way of operating optimal? Or can we do better? Is it still reasonable to prevent small RPAs from operating without special licences at very low levels at reasonable distances from airports? Is it justified by safety considerations? Let us know what you think in the comment.

About To70. To70 is one of the world’s leading aviation consultancies, founded in the Netherlands with offices in Europe, Australia, Asia, and Latin America. To70 believes that society’s growing demand for transport and mobility can be met in a safe, efficient, environmentally friendly and economically viable manner. To achieve this, policy and business decisions have to be based on objective information. With our diverse team of specialists and generalists to70 provides pragmatic solutions and expert advice, based on high-quality data-driven analyses. For more information, please refer to www.to70.com.