Early aircraft took off from any sufficiently large field that allowed take-off into the wind. As aircraft became large and faster, runways were build in multiple directions. Nowadays, new airports only have parallel runways. We explore the development of runway configurations and their effect on operation.

The first airfields where literal fields. A sufficiently large grassy area on which aircraft could always take off and land into the wind. The low mass and low speeds of the aircraft of the early 1900’s made them highly susceptible to crosswinds while at the same time not requiring a very long distance to take off or land.

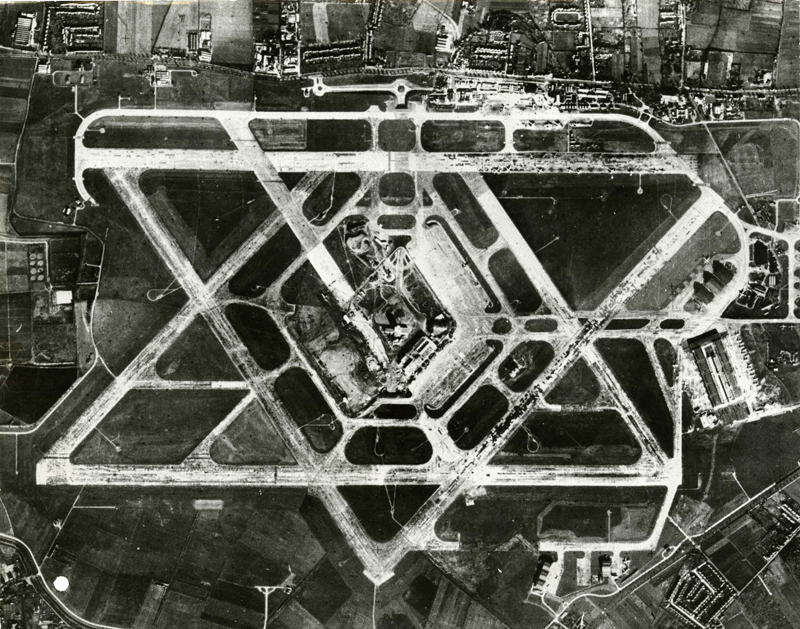

Between the first and second world war, aircraft grew larger and flew faster. These aircraft required longer runways. Few fields would be large enough to provide a possibility to land in any direction. This was exacerbated through the need for a hardened surface, at which point the real “runway” was born. To ensure that aircraft could mostly operate into the wind, the famous triangle airports of the second world war era appeared everywhere (see header photo).

With even heavier aircraft, higher speeds and longer runways, most airports after the second world war developed into parallel operations. At this point, aircraft speed, mass, navigation and control created more and more tolerance for cross-winds. While operation into the wind was preferable, an airport with only parallel runways was no longer an impossibility.

The advantages of parallel runways

Complexity: the parallel runways translate to a parallel taxi operating on the ground and flight operation in the TMA. The base of such a structure provides simplicity allowing high capacity operations without exceptional workload.

Safety: Intersecting runways have intersecting paths on the ground or in the air. Simultaneous use of converging runways requires extra monitoring.

Spatial planning: The parallel design reduces the amount of unusable space between runways. An airport with parallel runways typically uses less real estate.

Civil technical: The space between the runways is accessible and extendable: No need for under-runway access roads and (practically infinite) room to expand landside infrastructure between the runways.

Expandable: Expansion of the airport through further parallel runways is less complex.

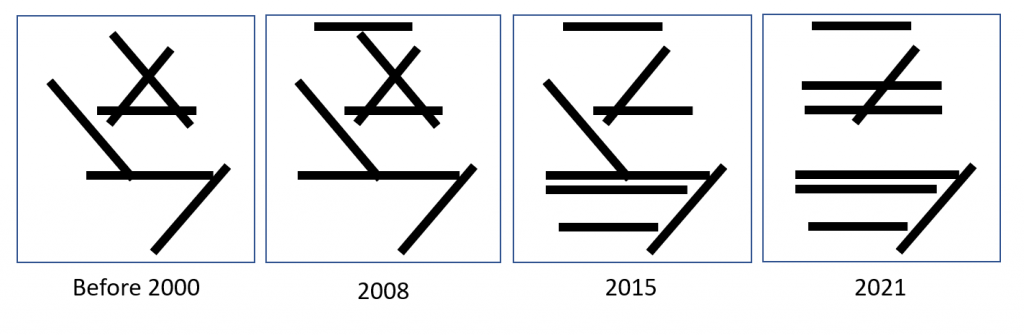

These advantages explain that all new airports have parallel runways and most airport expansions also increase the number of runways by adding parallel runways. A good example is Chicago O’Hare. This airport changed from a system of three pairs in three directions to a system with six parallel runways and only two intersecting runways.

Evolution of runway layout of Chicago O’Hare.

Why do crossing runways still exist?

However, airports with intersecting designs still exist. And only sometimes a crossing runway is eliminated, for example at Heathrow. Why then are intersecting designs still in use?

More sustainable capacity: While crosswind limits have risen over the years, they still exist and do occasionally close down airports with only parallel runways. This benefit only realises however, when multiple runways in a different direction are available as crossing runways limit capacity through interaction. Furthermore, the benefit depends on the amount of variation in wind direction at the airport.

Historic growth: Once such an operation exists, and the surrounding towns and cities expand, the interaction of aircraft noise and building permissions make it difficult to significantly alter the operation without large impact to the now grown surrounding community. Perhaps this aspect extends further in that the varying direction allows for much more spread of the impact of noise.

Demonstrated safety: Years of operations at large airports such as Amsterdam, JFK, Boston, Chicago O’Hare and San Francisco have demonstrated that safe operation of such runways is possible.

Are the advantages really that large?

The advantage of a more sustainable capacity seems large, but adaption to changing winds comes at a cost. Having more options introduces a volatility to wind conditions. That is, more choice leads to more uncertainty in the runway combination in use. Furthermore, the process of reconfiguration itself is costly; Since the old and new streams of aircraft on the ground and in the air may not be compatible, a temporal drop in capacity will result. Secondly, the reconfiguration is a high workload process for air traffic control on the ground and in the TMA. Finally, an altered runway direction may have a considerable effect on taxi times with associated impact on predictability for the airline.

Solving the predictability challenge

Having more options in runway configuration thus increases sustainability of capacity at the cost of predictability. Decision support tools such as To70’s runway forecast system may help in selecting a sustainable runway configuration for an entire day rather than optimising for shifting winds as the day progresses. These techniques support continued operation at those airports that will remain using intersecting runways for the foreseeable future.

About To70. To70 is one of the world’s leading aviation consultancies, founded in the Netherlands with offices in Europe, Australia, Asia, and Latin America. To70 believes that society’s growing demand for transport and mobility can be met in a safe, efficient, environmentally friendly and economically viable manner. To achieve this, policy and business decisions have to be based on objective information. With our diverse team of specialists and generalists to70 provides pragmatic solutions and expert advice, based on high-quality data-driven analyses. For more information, please refer to www.to70.com.

Image source:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/London_Heathrow_Airport#/media/File:Aerial_photograph_of_Heathrow_Airport,_1955.jpg